Even when we take a look at the book about the first five years of Anadolu Kültür’s activities, we come across a broad scope. Starting from the Diyarbakır Arts Centre and extending to Hakkari and its neighbours, Trabzon, Çanakkale, Kars, Armenia, Azerbaijan, exhibitions, film screenings, concerts, panels, memory studies, workshops, production support… What was the organizational plan you had in mind when you founded Anadolu Kültür twenty years ago, and what kind of contribution did you hope Anadolu Kültür would make to Turkey?

Osman Kavala: At the time of its foundation, we based Anadolu Kültür on the idea that art and cultural activities would improve mutual understanding, and that young people from different backgrounds living far away from each other could overcome their prejudices through working together. We thought that the narration, transmission and listening to the painful events of the past through art would encourage reconciliation/understanding processes that require or create significant changes within the country, a process which is expressed in foreign languages with the concept of reconciliation.

The establishment of an art centre in Diyarbakır and our work with artists from Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora also held a special meaning for us. For example, women from Diyarbakır and Trabzon staged a joint play, and there were performances in both cities. We held exhibitions encouraging dialogue with artists from the Armenian Diaspora, and organised concerts of the Turkey-Armenia Youth Symphony Orchestra with conductor Cem Mansur. These were the years when the democratization process was taking place in our country and the perspective to join the European Union perspective was still active. We believed that collaborating with European artists and institutions and organizing these activities in cities other than Istanbul would contribute to the process.

Such activities in the field of civil society are much more meaningful in a democratic environment, when the dynamics towards democratization are strong. When the political environment changes in a negative direction, the impact of these activities diminishes. It is not possible to bring about change through civil society activities in a political climate that favors segregation and feeds prejudices.

The indictment prepared against me alleges that, fifteen years after its foundation, Anadolu Kültür’s activities in relation to Kurds, Armenians and minority communities aimed to provoke them against the state. I believe that the ideological perspective that has now become dominant in government circles and the public sector with the change in the political environment in our country is reflected in these accusations.

On Anadolu Kültür’s website, it is written that after the 1999 earthquake, you left your active business life and turned towards civil society. What role did the İzmit earthquake and the economic crisis that followed play in this decision? Did these two important events have an impact on your efforts to strengthen local organizations and civil society?

Immediately after the 1999 earthquake, my colleagues and I launched an initiative called the Civil Coordination Centre to carry out support activities. Thanks to this initiative, I frequently visited earthquake zones and had the opportunity to get to know and work with people who had lost their loved ones and were in dire conditions themselves.

This experience made it clear that personally participating in civil society activities is more satisfying and exciting for me than business life. The fact that we had to give up some of our investments due to the economic crisis was also a factor in my choice to prioritise the field of civil society.

The Marmara earthquake showed us how unplanned urbanisation, arbitrary zoning practices, commercial concerns and collective irresponsibility lead to great human tragedies. It is painful that no lessons have been learnt from this disaster and that it has been forgotten that a major earthquake is expected in Istanbul.

The attempt to build a shopping centre in Gezi Park, which was declared as a gathering place after the earthquake, is a striking symbol of this situation. The Gezi movement, which was a resistance to aggressive construction and the commercialisation of public spaces, enabled the discussion of issues related to safe urban life and urban environmental rights from a solidaristic perspective. I hope that these discussions have strengthened awareness about the earthquake and the sense of collective responsibility that needs to be shared.

We know that you don’t write frequently. However, the article you wrote with lawyer Haluk İnanıcı that was published in Express in 2009 was a warning in terms of the principles of universal law during the “stormiest” days of the Ergenekon trial. You highlighted that the case was limited to the coup attempt against the government instead of focusing on counter-guerrilla activities, that the definition of various crimes had become vague, and that “trying to discover evidence departing from the suspect” was an “Inquisition practice” and that this would lead to a “witch hunt”. Why did you feel the need, in that article written in 2009, to emphasize the fundamental nature of the “rule of law” and what was the reaction?

Following the Ergenekon trial was instructive for me. The 2000s, as I said, was a period when accession negotiations with the EU had begun and anti-democratic laws were being amended. However, steps were not being taken to satisfy public opinion in elucidating the relations between security forces and criminal groups, which had been revealed following the Susurluk incident. An effort was not made to make state institutions transparent. The steps that led to and the actual assassination of Hrant Dink took place in plain sight. The arrest of certain individuals involved in shady activities and murders in the Ergenekon case initially gave me hope. However, the course of the trial and the fact that it targeted journalists and members of non-governmental organisations such as ÇYDD (Association for the Support of Contemporary Living) instead of focusing on the so-called “deep state” changed my mind.

According to Hitler’s principles, the main task of judges was not to protect the rights of individuals, but to ensure the survival of the nation, which was defined as a community. This manner of thinking paved the way for the arbitrary use of the law. Although our penal code has not been amended in this way, the prosecutor implemented the same approach.

Thanks to Haluk İnanıcı, I saw the unlawfulness of the judicial process more clearly and I wanted to warn optimistic people like me. I cannot say that the article had a significant impact, but I was happy to receive positive comments from some friends whose opinions I value.

I would like to add one more thing: The history of political trials in our country, as we know, is full of examples of violating the principles of law. I think it is a common observation that decisions contrary to universal law and human rights stem from the fact that judges and prosecutors have interiorised the perceptions of threat and danger nurtured in anti-democratic political environments and have developed a world view in line with these perceptions.

The Ergenekon case went beyond even such unlawful practices; it was centred on a comprehensive conspiracy theory that left the impression that the prosecutors and judges of the case could not have come up with it on their own. I felt that there was a difference compared to the past, but I failed to grasp that this case was the first example of the direct intervention of political circles in the judiciary.

This period that begun with the Ergenekon trial, continued in several other major cases in which Gulenists were influential, and with the State of Emergency declared after the 15 July coup attempt, the government institutionalised more forceful methods of intervention in the judiciary, effectively bringing an end to judicial independence. I think the fact that the absence of that assessment meant that our article remained incomplete.

In your defence in May 2021, you recalled Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. While describing the prosecution’s espionage allegations against you as “fantastic”, you made references to Nazi era trials. The article you wrote for the journal Birikim, in November 2019, on Sebastien Haffner’s book titled The Meaning of Hitler shows that you are giving more thought to this period. At what stage of your trials, which were interwoven with various levels of unlawfulness for five years, did you reflect on the power, law and society of the Third Reich?

I noticed some similarities in the first indictment, but my arrest on charges of espionage, followed by the second indictment, which included this accusation along with the allegation of participation in the 15 July coup attempt, made me think deeply of the practices of the Nazi era. As I said at the hearing, in Nazi Germany, the principle of nullum crimen sige lege, or “no crime without law” was abolished with an amendment to the penal code. According to the common conscience of the people, that is, according to the view point of the Nazis who supposedly represented the people, it was made an obligation to punish the actions of the person who deserved to be punished in accordance with that law with the main tenet closest to the accusations, even if his or her actions did not fit the definitions of offences written in the law.

According to Hitler’s principles, the main task of judges was not to protect the rights of individuals, but to ensure the survival of the nation, which was defined as a community. This manner of thinking paved the way for the arbitrary use of the law. Although our penal code has not been amended in this way, the prosecutor implemented the same approach. In order to criminalise my legitimate civil society activities, an offence of espionage other than the one defined in the law was constructed, thinking that espionage was the closest offence to accusations of being an ally of George Soros, aimed at me by the President and the MHP (National Movement Party) Chairperson.

Another element reminiscent of the Nazi era was the conspiracy theory in the second indictment that Open Society organizations were spreading cosmopolitan culture and corrupting national and local cultures and thus trying to dominate these societies. As is well known, the Nazis had put forward similar arguments against the Jews.

Let me add this: The Justification of the Decision for the sentence of aggravated life imprisonment against me, states it is based on a conscientious conviction. We see that this conscientious conviction, which is important in determining the degree of guilt of those who have committed a crime, by way of assessing the conditions under which they committed the act deemed a crime, has turned into an ideological conviction here, as in the practices of the Nazi period, and is used as a justification for punishing those who have committed non-criminal acts.

In their article on birartibir.org in March 2020, lawyers Kasım Akbaş and Tora Pekin refer to the concept of “Dual State” used in 1941 by Ernst Fraenkel, a lawyer in Berlin between 1933-1938, in relation to your case: On the one hand, the “state of norms”, where institutions and legal procedures appear to function, and on the other hand, the political sphere shaped by the arbitrary rule of those in power, the “state of privilege”. What does the definition of “dual state” mean to you instead of the conceptualisation of the “deep state”, the existence of which cannot be easily proven?

Fraenkel uses the term “dual state” to describe the dual functioning of the state that came under complete Nazi domination, otherwise the state is not divided into two. In a state of emergency, the measures taken by the Nazis “to ensure the survival of the state and to ensure the essential unity of the German people” override legal norms.

On the other hand, some legal norms are preserved in order to maintain the rational functioning of the capitalist economy, and the courts continue to rule according to these norms in economic or administrative disputes arising in these areas. In the political sphere, the state of emergency is permanent, while the activities required by the capitalist economic order must be carried out as usual, provided that they do not contradict the priorities of the political power.

I think Fraenkel’s concept of the dual state can also shed light on the functioning of the judiciary in our country. The judiciary, previously independent, albeit with certain ideological obsessions, has now come under the control of the political mechanism, as it was in the Third Reich. Through the interventions of the HSK (Council of Judges and Prosecutors), through prosecutors taking direct orders, and through the nomination of new judges and prosecutors with a perspective close to the government, political power has organically penetrated the judiciary.

However, this does not mean that legal norms have been completely overridden. In cases related to economic disputes, as well as in political cases that are not important for the government, the courts, especially the higher judicial bodies, take legal norms into account in their judgements, and there are members of the court panels who do so.

On the other hand, in matters and cases where the government takes sides, or indicates that it has taken sides, the aforementioned members cannot influence judgements, they can only seek to draw attention to unlawfulness through their dissenting opinions. I believe that this dual functioning has a functional rationality for the government, as it gives the impression that legal institutions are still functioning in the way they used to.

The concept of deep state does not fully suffice to explain this situation. The deep state describes the activities of the state that are invisible to the naked eye, that are not publicly visible, and the official, semi-legal institutions through which these activities are carried out. Since the use of the judiciary for political purposes also serves the consolidation of ideological hegemony and the creation of perceptions, it is very public, in full view of everyone; it is supported by reports of pro-government media that merely amount to propaganda.

In your article in Birikim, you state that today’s populist governments tend to dissolve public institutions in the name of the separation of powers and increase their political privileges and arbitrary practices. Do you think that the legal and political methods of the Hitler era are practices specific to that moment in history, or is fascism a political movement and ideology that transforms and exists under different disguises during different periods?

As you know, “fascist” is a word that Mussolini and his supporters used to call themselves. In ancient Rome, “fasces”, bundles of wooden axe handles, were carried in front of members of the higher judiciary as a symbol of the courts’ power to punish. The Nazi regime differed from Mussolini’s Italy in that it was more “fascist” in today’s sense. It would perhaps be an overgeneralisation to say that an ideology or political movement that emerged in the 1930s continues to exist today in disguise. However, it is a fact that there are common points between the populist movements we encounter today and fascism.

In the article titled “Eternal Fascism” in his book Five Moral Pieces, Umberto Eco describes the basic elements of fascism with the concept of “root-fascism” / “ur-fascism”. “Enemy” is one of them. Eco writes that there is an obsession with an international conspiracy in the ideology of root-fascism, that xenophobia is used to expose this, and that collaborators are sought internally.

Among elements of root-fascism, Eco also mentions the effort to create a unity of opinion by turning tensions created by differences in society into fear. Fraenkel has also identified that in National Socialist thought, the “enemy” is “the constitutive element of the political imagination”. He says that the mythos of a permanent state of emergency needs this concept: “If there is no real enemy, you have to invent one. Without enemies there is no danger, without danger there is no sense of community, without a sense of community there is no national community.” Eco concludes his article “Eternal Fascism” by saying that “our task is to point out every new symptom of root-fascism, every day and everywhere in the world”.

What do you read in prison, which books would you like to mention among those that have offered you dimensions you had not thought about before? What do you think these books say about the present, or the current “human condition”?

All well-written works of literature lead to a change in our view of the human condition, our thoughts and awareness delve deeper thanks to them. Here I discovered how useful it is to re-read the classics, many years after I first read them. Stefan Zweig says that he understood Montaigne’s viewpoint better when he re-read his works after experiencing the catastrophe of war. When I was detained, I spent two weeks in a small cell, some days with three or four other people. Reading Montaigne was very salutary at that time, and I continued to read him afterwards.

In this context, the great writer who has never left my mind is Shakespeare. Whenever I read him, I discover something new. It is very helpful to read Shakespeare for a better understanding of complex human situations as well as the sources of the evils that manifest themselves in human relations and politics, including what is happening in our country these days.

It was also helpful to read the books by Primo Levi, Jean Améry and, of course, Viktor E. Frankl, who had been in a Nazi camp, in order to make comparisons with my own situation and thus to keep my spirits up. Frans de Waal’s books have improved my thinking about our close relatives whom we call animals. But I think the book I mentioned earlier, Beyond Crime and Redemption by Jean Améry, had the most powerful effect on me in terms of triggering thought. He was imprisoned in Nazi camps, changed his German name when he came out, and years later chose to commit suicide, as some Jewish intellectuals who had a similar experience did. In Beyond Crime and Redemption, he describes the effects of his experience on him and accuses the German society, which was trying to recover from the devastation they suffered after the Second World War, of not showing a strong will to confront the crime committed. However, for me, what was most sobering was what he wrote about the Enlightenment. I would like to quote his words, which I have noted down in order to fully reflect on what he says:

Whenever I read Shakespeare, I discover something new. It is very helpful to read Shakespeare for a better understanding of complex human situations as well as the sources of the evils that manifest themselves in human relations and politics, including what is happening in our country these days.

“The concept of Enlightenment should certainly not be compressed into a very narrow framework, because as I understand it, it encompasses more than just logical deduction and empirical verification; it includes a willingness and ability to go beyond both of these to a phenomenological construct, empathy, an attempt to approach the limits of reason. Only if we fulfil, and at the same time transcend, the law of the Enlightenment, can we reach the spiritual spheres that la raison cannot take us to through depthless and inconclusive reasoning. Emotions? I have no objection to them. Where does it say that the Enlightenment must be free of emotions? It seems to me that the opposite is true.”

From these words, it is seen that Améry is pointing out that one should not be content with reasoning, and that the Enlightenment can be given its due through a way of thinking that tries to understand the situations of people who have had different experiences from us, who are different from us, and who use the ability of empathy.

The theses developed in Antonio Damasio’s books, which I recently read, made me think about Améry’s writings again, more deeply. In his books Searching for Spinoza and Descartes’ Fallacy, he explains that emotions support reasoning based on justification. He writes that a reasoning free of feelings and emotions leads to deviations and can harm the rationality that makes us human, our internalisation of social consensus and ethical rules. Damasio says that the experience of spirituality, which is experienced in the mind when certain emotions come together, can arise from prayer and worship, while the focus of thought on nature, scientific discovery, an important work of art can also create emotions that stimulate this experience.

Thinking along these lines, I conclude that there may be a relationship between the transformation of Enlightenment thought into “depthless and inconclusive reasoning” that Améry warns us against, and the Enlightenment’s becoming an ideology disconnected from art and literature that provides aesthetic experience and develops the ability of empathy. In ways of thinking dominated by ideology, reasoning is based on abstract models that are free from emotion. In some cases, the high goals and stimuli contained in ideologies and the assimilation of emotions into collective expressions of emotions that focus on these goals can disrupt the healthy interaction and balance between thought and emotions. If this idea is correct, I think we can speak of an ideologising effect for socialism, and even for religious beliefs, which makes it difficult to think deeply about the human condition and to reach spiritual spaces.

The Ottoman Empire shared a common fate with the German Empire in World War I and was defeated. However, it did not suffer post-war sanctions and economic depression as severely as Germany, nor did it take part in World War II. In your opinion, what are the similarities and differences between these two states, which were once allies, and how is this shared historical period reflected in today’s society?

Undoubtedly, it is a moral responsibility for every individual to obtain information about recent history from different sources, to critically examine the actions of the state of which one is a citizen, which have resulted in severe victimisation and mass atrocities, and to take a stand. However, as is well known, it is not possible for a society to face its past through individual efforts; it is necessary for the government to pursue a corresponding policy regarding historical memory and for political actors to create an environment of debate that encourages this. The dominant discourses in politics and civil society in Turkey do not encourage a frank acknowledgement of what happened during the aforementioned period. On the one hand, there is a discourse that ignores the events that they think will tarnish the glory of the Ottoman imperial past based on conquests, and claims that Muslims will never commit shameful acts. The historical narrative, which focuses on the War of Independence against the occupying forces and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey as a secular nation-state, is not interested in the imperial past of the Ottoman Empire or the fact that Greeks, Armenians and Kurds were autochthonous peoples of Anatolia, because that line of thought would not be in line with the anti-imperialist emphasis.

The fictitious idea that I organised and led protests in 79 provinces with the participation of millions of people is flattering for someone of my age, but it is so irrational that I cannot even imagine for a moment that I managed to do such a thing. However, the fact that it is so extraordinary does not mean that this claim provides no functional rationality for the government.

It is also necessary to take into consideration differences between the decisive political dynamics of the two events. Germany started the Second World War, and as a result of a series of military victories, took control of almost all of continental Europe up to Russia. Had it not attacked the Soviet Union, with which it had previously signed a non-agression pact, its domination of Europe might have been permanent, as Sebastian Haffner points out in The Meaning of Hitler. Again, as Haffner points out, Hitler’s plan to cleanse Germany and Europe of Jews, which turned into a complete genocide after their defeat by the Soviets, was an ideological/racist obsession that had no rationale in terms of Germany’s goal of becoming the dominant power, and was even detrimental to it.

As is well known, the Jews were not party to any territorial conflict in Germany or anywhere else in Europe; the secular Zionist movement, which advocated the creation of a Jewish nation-state, was propagandising for Jewish emigration to Palestine. When the Second World War ended in defeat for Germany, German society was forced to recognise that the Nazi regime was guilty not only for the Holocaust, but for all the disasters that befell Europe and Germany, and that the citizens of the German state who supported it and did not speak out against the discrimination and violence against the Jews were also responsible.

Nevertheless, it took until the ‘60s, when Germany had recovered from the trauma of destruction, division and the stigmatisation by the rest of Europe as a criminal state, that the German state and society were able to come to terms with its Nazi past. The acknowledgement of massacres committed by Germany in Namibia during the First World War, recognised by some as genocide, is much more recent.

The conditions of the First World War were different. The Ottoman Empire had no role in the outbreak of the war. The Committee of Union and Progress government joined the war because it saw it as an opportunity to regain the lost territories in the Balkans, but the war became an increasingly severe tragedy for the Ottoman Empire. The heavy losses in Gallipoli and Sarıkamış, the advance of Russian troops in the east, the occupation of Antep, the extensive Greek offensive after the defeat, traumatised the Ottoman state administration and Muslim subjects for the first time in its history with the trauma of major territorial losses in Anatolia, and this experience was engraved in public memory.

Since the Republic of Turkey did not participate in the Second World War, perceptions stemming from the experience of the First World War continued to influence the attitudes of those in political power and state positions towards Europe and minorities. According to Turkey’s official theses, the deportation of Armenians was a necessary security measure taken during the war. However, when the political dynamics of that period and the conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and Europe and Russia are taken into consideration, it becomes clear that the real security concern was not related to the war. In this period, when the borders of new nation states were being defined after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the loyalty of minorities with the same ethnic or religious affiliation as the peoples of the neighbouring countries to their states seemed problematic. Russia had declared itself the protector of Orthodox Christians in Anatolia. The 1878 Berlin Conference’s decision to demand administrative arrangements to improve the conditions of the Armenian population in six provinces in Eastern Anatolia and to assign two European commissioners to oversee these arrangements was undoubtedly seen by the Ottoman administration as an imposition of autonomy that would lead to the establishment of an independent Armenian state.

During the reign of Abdülhamid II, Armenian rebellions in Eastern Anatolia were suppressed in a bloody manner and Hamidiye Regiments were established by assembling militia recruited from Kurdish tribes, in order to put pressure on Armenians. The policies of the reformist Committee of Union and Progress, which had received the support of religious minorities in the first years of their political power, had close relations with the Dashnak Party [Dashnaktsutyun, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Party], and advocated the idea of a citizenship that transcended ethnic and religious identities, changed when the war broke out, and the Dashnak Party, which had adopted a policy of neutrality in the war, became estranged from them, and adopted the line that the Greek and Armenian population could not be relied upon to create national unity. Plans to reduce this population had already been prepared before the war, and incidents of intimidation and kidnapping had taken place in some regions. As it is understood from the statements of Cemal Pasha, the aim of the deportation decision was to eliminate the threat of the establishment of an Armenian state in the east, which was also on the agenda with the Treaty of Sevres.

Today, the Sevres syndrome feeds on the Kurdish question, which, like the Armenian question, has a territorial character. The fact that the US supports the PYD in Syria and that European governments have not listed the PYD as a terrorist organisation is perceived as an indicator of the West’s divisionist ambitions. For this reason, I think in order to create a climate of sincere public acknowledgement regarding the genocide, or the 1915 Massacre of Armenians, as it is known in our country. Peace must be established with the Kurds in our country, in Northern Iraq and Northern Syria, and the impact of the widespread concern that the West is trying to divide our country must be reduced. Of course, we also need to become a state of law.

It is clear that the sentence passed against you does not resonate with the public conscience. Moreover, the verdict against you and seven of our friends, directly condemned Gezi, a social movement in which millions of people participated that could not have been organised in advance. What kind of “fantastic” situation do you see here?

In France, anyone who claimed that a few individuals or George Soros had organised and financed the Yellow Vests protests would have been treated as a lunatic. The fictitious idea that I organised and led protests in 79 provinces with the participation of millions of people is flattering for someone of my age, but it is so irrational that I cannot even imagine for a moment that I managed to do such a thing. However, the fact that it is so extraordinary does not mean that this claim provides no functional rationality for the government. Putting a few people in jail, as you say, sends a message to millions of people.

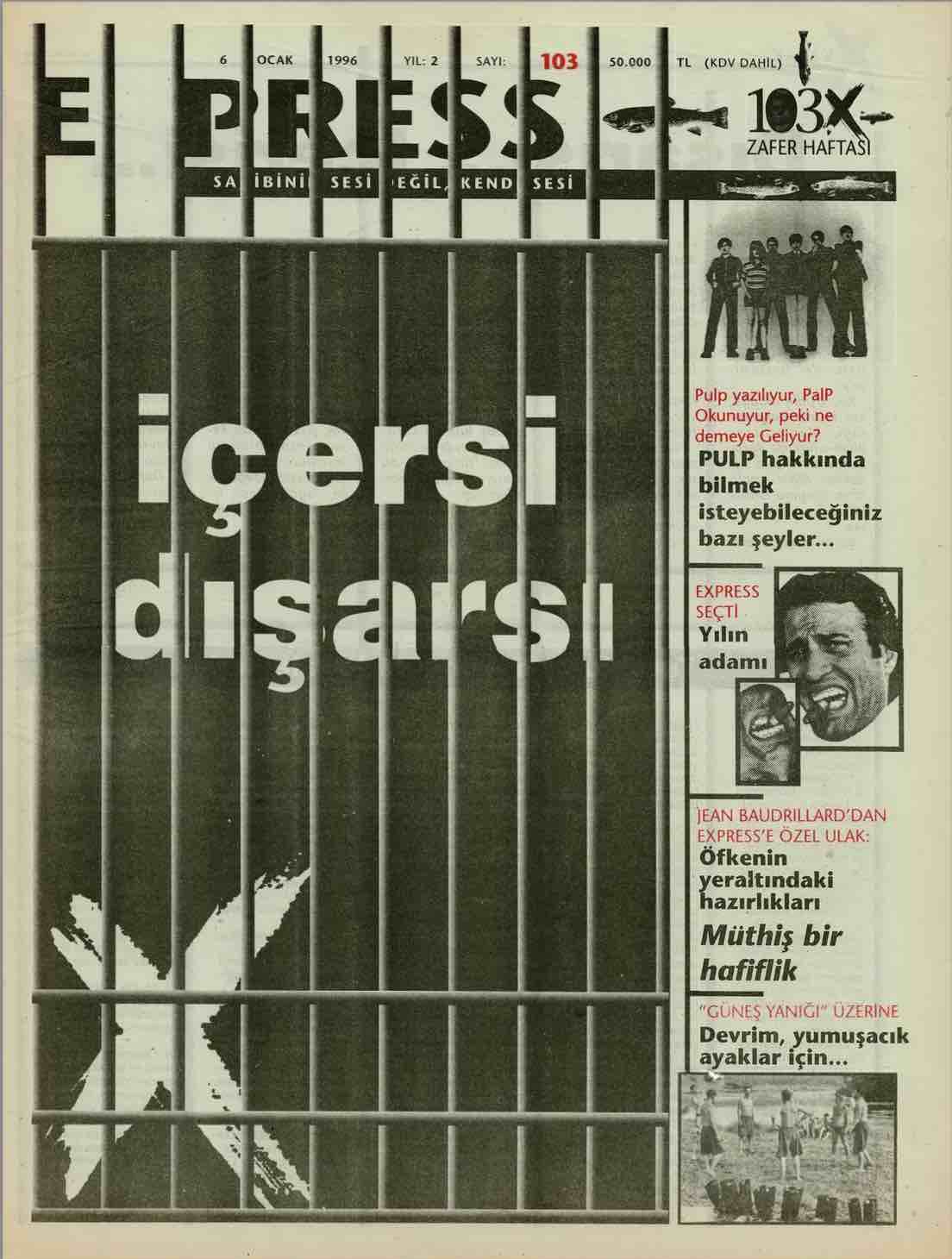

We participated in the solidarity book prepared for you in 2019 with a cover of the weekly Express from 1996. The cover featured Bülent Erkmen’s work titled “İçerisi / Dışarısı” (“Inside / Outside”). In 1996, four prisoners had been killed in an assault on political prisoners in Ümraniye Prison, and protests had spread to other prisons. The situation of the “inside” is not much different today. But, as Bülent Erkmen so aptly points out, the “outside” is no better than the “inside”. How do you view the “outside world” from “inside”?

If I had been released, of course I would have been very happy to be reunited with my wife, family and friends. However, I think I would not have been able to feel the joy of freedom, of being free. There has never been an environment of complete freedom in Turkey, but in the climate of state of emergency that began and continues with the State of Emergency, being called to testify, being detained, being arrested has become completely ordinary. A sword of Damocles hangs over the head of every citizen. Therefore, I completely agree with Bülent Erkmen’s assessment.

Founded towards the end of 2008, Depo has made great contributions to Istanbul’s cultural life. Just as the activities of Anadolu Kültür opened up to the Caucasus, Depo has formed an artist network that includes Eastern Europe and the Balkans. The contemporary artists of Istanbul have shown solidarity with you during your detention; and many bus trips have been made to Silivri. One of the issues that has recently occupied the contemporary art scene is the Beyoğlu Culture Route Festival. The street festival, organised by the Ministry of Culture and the Beyoğlu Municipality, would perhaps have ended in the middle of the shops in the Topçu Military Barracks if Gezi Park had not been defended. This brings us back to art and its relationship with the city and its inhabitants. Taking into account the years you spent with Depo, what kind of Beyoğlu, Istanbul and urban identity do you have in your heart?

Istanbul is a mega city whose demographic structure is constantly changing due to migration, growing and becoming more and more crowded. It does not seem possible to talk about a common urban identity. Beyoğlu, on the other hand, is a region that reminds the cosmopolitan cultural history of Istanbul and keeps it alive with some of its elements. It has the characteristic of being a place where Istanbulites from different circles, different neighbourhoods, different classes, and of course, foreigners visiting Istanbul are in demand. I think it is important for contemporary urban culture that Beyoğlu is a common space used for going to the cinema, exhibitions, concerts, dining and having fun. Gezi Park has a similar function. Parks in the centre of the city are places, in fact the only places, where people can go and spend time as long as they want, rest, chat and not pay for it. Gezi Park allows people of all ages and classes who live and work around Taksim to take a breath and enjoy life to some extent.

As of now, you have been in prison for five years. What have you missed doing the most? For example, you probably don’t have a choice of music, what music did you like, what music or other things do you long for? What would you like to do first when you are free?

Symphonic music and concertos of great composers have the most influence on me. But I enjoy listening to all kinds of good music, including Turkish classical music and folk melodies. The works that marked the years when I became interested in music and world affairs also have a special meaning. I think that this music reflects and reminds me of the optimistic mood of that period, shared by the ‘68 generation, whose influence went beyond the borders of Europe, that the social and political order would change for the better. Unfortunately, this period of optimism did not last long…

I can read the books I want here, I can watch festival films on TRT2. What I lack the most is not being able to listen to the music I love, or rather, not being able to listen to the music I love with my wife. When you listen to it with the people you love, with your friends, no matter what kind of music it is, even if it is melancholic, it gives you the joy of life and makes you feel that sharing life is a beautiful thing.

Let us leave the last word to you: What would you like to say to the readers of Express, and to all who know that your detention is an unlawful imprisonment, who are looking forward to your release?

Being imprisoned for five years on charges that are not only without evidence but also extremely illogical makes you question your relationship with the society you live in. You think that this is an extraordinary case of lawlessness, and you find it strange that people, especially those who know you, continue to behave as if everything is normal. What prevents this mood from turning into cynicism and alienation from society is the knowledge that there are those who react to your captivity, even if they cannot do anything about it, and the feeling that you are part of a society that cares about peace, freedoms and equality. In this respect, I feel lucky. I believe that the Express magazine team and its readers are among the founding constituents of such a society.

1+1 Express, issue 181, Autumn 2022

Translated by Güner Yavaşer